As an athlete or physically active ‘competitive’ person, are you the slightest bit confused as to whether you should be consuming a diet rich in carbohydrate, or restricting carbohydrate intake and leaning more towards fat and protein as your major nutrient sources? There are certainly some mixed messages out there, so we feel that this topic desperately needs to be discussed in a balanced fashion to clear up any ambiguity.

We’ve known for a long time that carbohydrate is an essential fuel source for endurance performance. Without sufficient carbohydrate available for our working muscles, we can’t perform well in competition and struggle to complete hard training sessions. So, when performance is the goal, it is vital to fuel with carbohydrates before, during and after competition.

Our nutritional approach to competition, where the main goal is to maximize our performance and achieve our athletic potential, isn’t necessarily always the best approach to take when training, where the main goal is to put the body under physiological stress to stimulate it to adapt, recover and become stronger. In this article, we are going to look at how we can use a nutrition strategy called ‘training low’ or ‘fasted training’ to maximize the response we get to selected training sessions.

High Carb, Low Carb and Fat Adaptation

There is a big fight going on in the sports nutrition arena at the moment, with two sides arguing over how endurance athletes should best fuel training and competition. On one side is a group arguing that a low carbohydrate, high fat diet is the best approach, whereas the other is arguing that a high carbohydrate approach is best.

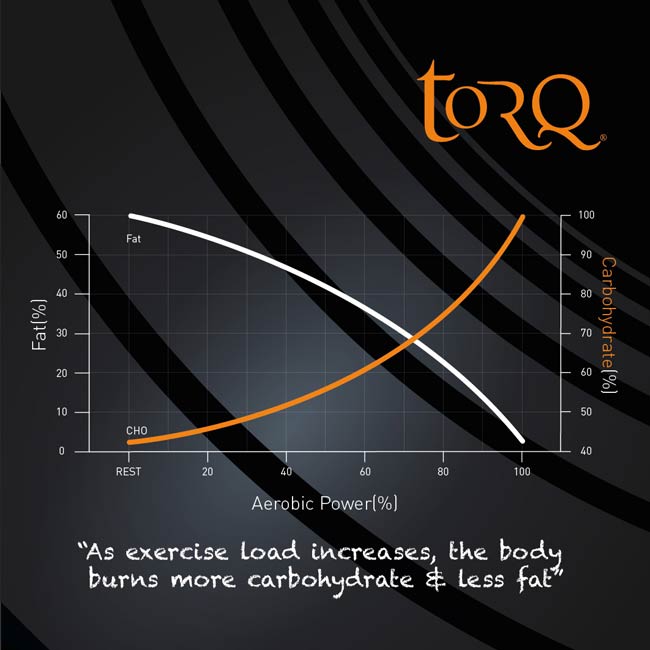

When we look at the fuels that our bodies utilize to create the energy for our working muscles, we use two predominate sources - fat and carbohydrate.

At one extreme, we have abundant stores of fat as fuel. For example, a relatively lean 70kg/155lb athlete with 10% body fat would have in the region of 63,000Kcal of fat stored, which would be enough to fuel a low intensity walk of a few thousand miles without the need to refuel.

Carbohydrate on the other hand is a much more finite fuel reserve. A trained athlete who was well fueled and rested would only have in the region of 2000-3000Kcal of carbohydrate stored within their muscles and liver as glycogen, and this is only enough for as little as 60-90 minutes of high intensity exercise.

When we look at how our bodies utilize these fuels, as illustrated in the graph above, fat is the predominant fuel source for low intensity exercise, with the relative contribution of fat (white line) decreasing as aerobic power increases. On the other hand, the contribution of carbohydrate (orange line) is relatively low until higher exercise intensities are reached. When we start exercising at above 80% of our aerobic power, we are almost entirely reliant on carbohydrate (think 'race pace'). On the positive side, carbohydrate is a much easier fuel source for the body to use at high intensity, as it requires less oxygen to breakdown - overall a greater fuel economy, but as explained above, it is a finite resource.

Through training and nutrition, we can increase the contribution of fat as a fuel source to exercise and this is a key area of interest for many athletes, as the more we can rely on our abundant fat reserves, the longer our glycogen stores will last for, which will delay the point at which we blow up/hit the wall and get the associated catastrophic drop in performance. ‘Blowing up’ or ‘Hitting the wall’ or ‘Bonking’ are all expressions used to describe the painful, debilitating and performance-crippling effects of running out of carbohydrate when exercising! (the brain shuts down the 'body' to preserve remaining blood glucose for its precious self...)

Low Carbohydrate High Fat Diets (#LCHF) and Fat Adaptation – In a bid to increase fat burning, one relatively extreme approach that some athletes have adopted is to follow a low carbohydrate, high fat diet. By reducing the amount of dietary carbohydrate to <25% of total energy intake, in as little as 6 days, the muscles 'retool' to be able to utilize fat at a much higher intensity. This process is often referred to as ‘Fat Adaptation’. This has benefits in that it allows us to more effectively tap into the abundant reserves of fat stored within the body and use fat at a higher relative exercise intensity.

There are some significant downsides though. Even with a very well trained fat metabolism we can only use fat up to around 60-75% of our aerobic power, which effectively means that we remove our ‘top gears’. By limiting the carbohydrate in our diet to relatively small amounts, we also switch off our ability to utilize carbohydrate, which means that even when we top our glycogen stores back up before competition, we cannot use carbohydrate effectively and our ability to perform high intensity efforts is destroyed. It’s these high intensity efforts that often win races or allow us to beat our competitors. So, despite the proven benefits of Fat Adaptation, this process does lead to a decrease in overall performance. This is reflected in the scientific literature, where to date, no studies have convincingly shown an increase in endurance performance as a result of consuming a low carbohydrate high fat diet. Reducing carbohydrate in the diet may also put you at a greater risk of illness and infection as our immune systems prefer to use carbohydrate as a fuel source.

High Carbohydrate Diet – This is the more traditional approach to training nutrition and reflects the approach that many athletes have to competition. All training sessions are completed with the goal of ensuring high carbohydrate availability (i.e. fueling before/during/after). This allows high volume, high quality training to be completed, with rapid recovery. It replicates the demands of competition, limits the chance of over-training and helps the gut to adapt to a high carbohydrate intake, reducing the risk of stomach issues during competition. Carbohydrate is also vital for optimal muscle and cognitive function, so this approach helps to ensure high quality training and reduces injury risk.

However, we need to marry this with the benefits that can be achieved through fat adaptation training, where the diet is very low in carbohydrate, but where optimal carbohydrate fueling is conducted every session to ensure best performance. There is a catch though - fueling optimally with carbohydrate starts to reduce the body's ability to utilize fat as effectively. Naturally, the body will use carbohydrate in preference to fat, when carbohydrate is readily available.

So, you may be wondering which approach is best for training? Well, as with many things in sports science and life in general, it’s not black and white and the answer lies somewhere within the middle ground. A combination of training with both high and low carbohydrate availability can help us to develop a body that can use both carbohydrate and fat effectively (often referred to as metabolic flexibility) which ultimately will be the best way to enhance our performance and improve as endurance athletes.

For the next part of this article we are going to take a detailed look at exactly what ‘Fasted Training’ or ‘Training Low’ as it’s commonly called, actually is, what the advantages and disadvantages might be, and how you might fit this nutritional strategy into your own training program.

What is Training Low/Periodized Carbohydrate Intake?

TL is a form of nutritional periodization, much in the same way that your training sessions aren’t the same day in day out, your nutrition shouldn’t be either. Essentially we are looking to fuel specifically for the work required, matching the amount of carbohydrate that we consume to the demands of the training sessions that you are completing. For example, if you are completing a high intensity interval type session, then it needs to be well fueled with carbohydrate. On the other hand, if you are completing a low intensity training session, you don’t necessarily need to consume lots of carbohydrate and can achieve benefits from carefully limiting carbohydrate intake. This means that although some training sessions would be deliberately focused at maximizing physiological adaptations through adopting a low carbohydrate regimen, others would need to be optimally fueled to achieve the associated benefits. Competition should always be completed with high carbohydrate availability, as put simply, carbohydrate is king for performance. This is often referred to as the ‘Train Low/Compete High’ paradigm for nutritional periodization.

TL means exercising with low carbohydrate availability – limiting the fuel’s supply to the working muscles. This can be achieved through

- a) Starting a training session with low glycogen stores, by depleting/reducing them prior to starting the sessions and/or

- b) Limiting the consumption of foods containing carbohydrate before/during a training session. Some examples of how this might look in practice include:

- Training 6-10 hours after your last meal – often referred to as fasted training

- Completing an endurance training session longer than 60-90 minutes without consuming any/sufficient carbohydrate during the session

- Training before breakfast, having not eaten since the previous day

- Training twice a day and not refueling with sufficient carbohydrate in-between sessions – it can often be impossible to replenish glycogen stores with less than 8 hours between sessions

- Training in the evening and again the following morning with limited/no carbohydrate consumed in between

What are the potential advantages of ‘Training Low’?

Training low is not some magical training technique that will suddenly turn you into a super elite athlete after a couple of sessions, but used appropriately can help you to get a little bit more out of some of your training sessions, which when completed consistently over a period of time, could lead to some improvement in your endurance performance.

One of the most important adaptions to endurance training is an increase in the number of our mitochondria and this occurs through a process called ‘mitochondrial biogenesis’. Mitochondria are basically the engine of the muscle cells (remember the 'power house of the cell' taught in school...), responsible for burning both fat and carbohydrate. The more mitochondria that we have, the better our exercise capacity (i.e. with more mitochondria we can perform more work over a shorter period).

The stress associated with exercise leads to our muscles sending out signals (or ‘gene expressions’ as its referred to in science). These signals dictate how the muscles respond and adapt to that session. In the case of training with low carbohydrate availability, the increased stress response from not having carbohydrate available as a fuel, leads to an increase in signals associated with mitochondrial biogenesis and means that training low results in a greater amount of mitochondrial biogenesis than training with a high carbohydrate availability. This effectively means that you get more bang for your buck when it comes to training with low carbohydrate availability. Several studies have now shown that completing selected sessions with low carbohydrate availability can lead to positive training adaptations associated with fat metabolism, (of which mitochondria biogenesis is a key one), to a greater degree than training with high carbohydrate availability for all sessions.

It is important to note, that although very important, the increase in mitochondria is only one of many adaptations associated with endurance training and if we were to train low all the time, we wouldn’t get any of the key changes associated with utilizing carbohydrate from ‘Training High’ (TH). It is therefore important to balance both high and low carbohydrate training and to ensure high carbohydrate availability on competition day to ensure optimal performance. It runs deeper than this too, because failure to perform high intensity endurance and anaerobic interval sessions as part of your periodized training plan will leave you ill-prepared for competition. The key to TL is to tap the benefits of mitochondrial biogenesis without destroying your ability to burn carbohydrate and your performance 'gears' in general!

TL is a relatively new and exciting topic in the sports science research, but being a fledgling area of investigation means that a lot of questions remain unanswered. Very little is known about how best to structure this type of training into an athlete’s schedule overall. With this in mind, it stands to reason that TL must be very carefully managed, if considered at all, particularly for athletes who may already train low ‘accidentally’ because of heavy training loads. At the end of this article, we will of course communicate our recommendations based on our assessment of the available information.

What are the disadvantages of TL?

There are several disadvantages to completing TL sessions, which include:

Training Intensity – Training low makes sessions feel much harder than training with high carbohydrate availability, so even a relatively easy session can be perceived as being very hard! Because the training experience can feel so unpleasant, motivation can drop and training can end up feeling like a chore rather than a pleasant developmental experience. It also makes it very hard/impossible to complete intense training sessions, so it makes sense to only complete relatively low intensity training sessions when training low.

Protein Breakdown – Training low leads to an increase in the breakdown of muscle protein for use as a fuel (ironically, your body converts protein into carbohydrate at an energy cost. It’s called ‘gluconeogenesis’). If fasted training is performed frequently, this can accumulate into a significant loss of muscle, which will have a negative effect on your performance.

Immune Function – Performing unaccustomed, long duration or high intensity training sessions in a low carbohydrate state will put your immune system under significant stress, leaving you at much greater risk of illness and infections, which will clearly set back your training.

Recovery – Once you deplete your body’s stores of glycogen, it can take up to 24-48hrs consuming a high carbohydrate diet to fully replenish them. If you are completing a training session with low glycogen stores and have limited time before your next high intensity training session where carbohydrate is needed, a fasted session could compromise your performance during the following session.

How to structure TL sessions into your own program?

Here are a few key areas to address when considering programming TL sessions for an athlete:

How Often? – For athletes completing 5-6 days of training per week, undertaking multiple training sessions within a day, or having a generally high training volume, training low is inevitable, as it can be a challenge to consume sufficient food to meet the carbohydrate requirements of exercise. In this scenario, there is little need to program low training sessions into your week as it is likely to occur anyway. A focus on optimal fueling is likely to be the best approach and an awareness of when your glycogen stores might be low, can help you to better manage the negatives of training low. Please note that if this situation sounds familiar to you, you should turn the sentiment of this article on its head and ensure that you schedule enough TH sessions into your program.

For the average athlete with limited time to train (say 3-4 sessions a week totaling 4-5 hours of training), it is important to maximize the time you have available by creating the greatest training stress possible. The inclusion of a 1-2 hour TL session could bring about aerobic benefits similar to a much longer well-fueled session, so is the ideal approach for time-starved endurance athletes. However, limiting it to around 1-2 sessions at most will help ensure the balance between TH and TL training.

Training Intensity – Training low will increase the perceived exertion of a training session. It’s also impossible to tap into the anaerobic (high power output) system without a good supply of carbohydrate. To prevent this influencing the quality of the session, it is important to choose sessions that are not too prolonged or intense in nature. As mentioned earlier, an all-out interval session would be almost impossible or highly compromised when in a TL state, but a 1-2 hour low intensity ride would be perfectly targeted. Drinking a strong black coffee before the session, can help you through these sessions because of the benefit that caffeine can have on performance (mental), particularly when fatigued. Rinsing a carbohydrate drink around your mouth without swallowing it has also been shown to help to reduce the perception of effort when glycogen stores are low, but don’t expect any miracles if you’re going to try this (Kasper et al., 2016).

Immune Function – A lack of carbohydrate can put your immune system under significant stress and leave you more at risk of illness and infection. If you complete the session well hydrated and avoid any unaccustomed training sessions, you can help limit the negative impact to the immune system and reduce the chances of picking up an illness or infection.

Protein Breakdown – Consuming around 20-25 grams of a lean protein source, such as 2-3 scrambled eggs before a session can help to offset the breakdown of protein during a TL session and help keep hunger at bay.

Recovery Meal – Training in a low state can help stimulate the muscles to respond and adapt in a way that is going to be advantageous to your aerobic system, however, for these adaptions to occur the body doesn’t just require the training stimulus, it also requires the nutrients for these adaptions to take place. It is therefore important to follow-up the training session immediately with a high-quality carbohydrate and protein recovery drink/meal to ensure the body has the nutrients required to create these adaptions.

Recovery Time – Completing a TL session can increase the amount of time it takes to recover in comparison to a well-fueled session, so you will need to consume a carbohydrate and protein-rich diet for 24-48 hours if you’re wanting to follow up with a useful high intensity exercise bout. Selecting a TL session prior to a rest day would represent the ideal option. For this reason, it may also be best to avoid this type of training around competition too.

Take Home Message

TL is a relatively new area of research and we can’t pretend to have all the answers, but we have drawn the following conclusions, which we hope will help you to make the right choices:

If you’re time-limited, periodizing 1-2 TL sessions per week into your regimen may provide aerobic benefits over a 1-2 hour period that would otherwise require a longer ‘fueled’ session. Combine these TL efforts with 2-3 well fueled sessions.

If you’re an accomplished athlete with a significant amount of time available for training, you could still benefit from some TL sessions if you take some time to analyse at which points during your schedule your carbohydrate stores are likely to be naturally low, despite good fueling practices. These would tend to be at the end of a run of high load training, leading up to a rest day and we feel that this should be an ideal time to put a ‘Low’ training session into your schedule. You can then follow it with a rest day, high carbohydrate diet and get back down to business. Be aware that if you’re not currently fueling your training properly, you’re likely to get much bigger rewards by paying attention to this than any committed TL sessions.

If you’re a complete beginner or novice athlete, get a solid few months of training under your belt before you even start to consider something like this. A focus on optimal fueling will help you enjoy your training and likely get more out of it in the early stages of your athletic career.

To summarize, TL is a tool that can help you to get more out of your training, but don’t expect magical results from it. The downsides must be very carefully managed to ensure that this method doesn’t negatively impact your training and remember, the key is, as with many things in life, all about ‘balance’. Also (and this can’t be stressed strongly enough) many people don’t fuel their training sessions properly anyway and are therefore undergoing a TL regimen without even realizing it! Although this may provide associated benefits such as mitochondrial biogenesis, their performance will suffer because of inadequate fueling for many of their sessions and lack of metabolic flexibility. These people would make huge gains through consuming more carbohydrate ahead of and during the training sessions that really depend on it as a fuel source. The vast majority of people who haven’t followed a structured fueling regimen before and have gone on through our advice to increase their intake of carbohydrate-rich foods and use TORQ products, have made significant performance gains through increasing carbohydrate availability. Therefore, if you are going to schedule some TL sessions into your routine, it’s vital that you plan them properly and think about the bigger picture. A random approach is unlikely to get you very far and you would be much better off sticking to a high carbohydrate diet and fueling every session properly.

References

Bartlett, J.D., Hawley, J.A., Morton, J.P. (2014). Carbohydrate availability and exercise training adaptation: too much of a good thing? European Journal Sports Science. 15(1):3-12. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2014.920926.

Bartlett, J. D., Louhelainen, J., Iqbal, Z., Cochran, A. J., Gibala, M. J., Gregson, W., … & Morton, J. P. (2013). Reduced carbohydrate availability enhances exercise-induced p53 signalling in human skeletal muscle: implications for mitochondrial biogenesis. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 304(6), R450-R458.

Hulston, C. J., Venables, M. C., Mann, C. H., Martin, C., Philp, A., Baar, K., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2010). Training with low muscle glycogen enhances fat metabolism in well-trained cyclists. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(11), 2046-2055.

Kasper, A. M., Cocking, S., Cockayne, M., Barnard, M., Tench, J., Parker, L., … & Morton, J. P. (2016). Carbohydrate mouth rinse and caffeine improves high-intensity interval running capacity when carbohydrate restricted. European journal of sport science, 16(5), 560-568.

Lane, S. C., Camera, D. M., Lassiter, D. G., Areta, J. L., Bird, S. R., Yeo, W. K., Jeacocke, N.A., Zierath, J.R., Burke, L.M., & Hawley, J. A. (2015). Effects of sleeping with reduced carbohydrate availability on acute training responses. Journal of Applied Physiology, 119(6), 643-655.

Marquet, L. A., Brisswalter, J., Louis, J., Tiollier, E., Burke, L. M., Hawley, J. A., & Hausswirth, C. (2016). Enhanced endurance performance by periodization of CHO intake:“sleep low” strategy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. doi, 10.

Marquet, L. A., Hausswirth, C., Molle, O., Hawley, J. A., Burke, L. M., Tiollier, E., & Brisswalter, J. (2016). Periodization of Carbohydrate Intake: Short-Term Effect on Performance. Nutrients, 8(12), 755.

Morton, J. P., Croft, L., Bartlett, J. D., MacLaren, D. P., Reilly, T., Evans, L., … & Drust, B. (2009). Reduced carbohydrate availability does not modulate training-induced heat shock protein adaptations but does upregulate oxidative enzyme activity in human skeletal muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology, 106(5), 1513-1521.

Stellingwerff, T., & Cox, G. R. (2014). Systematic review: Carbohydrate supplementation on exercise performance or capacity of varying durations 1. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 39(9), 998-1011.

Van Proeyen, K., Szlufcik, K., Nielens, H., Ramaekers, M., & Hespel, P. (2011). Beneficial metabolic adaptations due to endurance exercise training in the fasted state. Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(1), 236-245.

Yeo, W. K., Paton, C. D., Garnham, A. P., Burke, L. M., Carey, A. L., & Hawley, J. A. (2008). Skeletal muscle adaptation and performance responses to once a day versus twice every second day endurance training regimens. Journal of Applied Physiology, 105(5), 1462-1470.